Ted Riethmuller

I was overseas when Alan got married to Pauline. This was back in January 1967. It was a pity because I missed one of the social occasions of the year – for the Brisbane leftwing community at least. Many years later we were talking about it. ‘I suppose Alan, the reception was held in the Waterside Workers Hall?’, ‘No, that wasn’t available so we were going to have it in the Communist Party hall in St Paul’s Terrace. But a few days before it was petrol bombed so we couldn’t use it.’

‘That sort of thing happened a lot in those days.’ I said, thinking back to a time in April 1972. I was attending a meeting in those premises when a bomb went off down stairs. It blew out the windows and filled the place with smoke. A couple of fascists had placed a few sticks of geli, lit the fuse and pissed off. Gary John Mangan stood trial but he got off of course. The common belief was that Mangan laid it on the line to the government, that if brought to trial he would tell what finance and other help they got from the police. Mangan claimed the case was fixed by Special Branch. When I told this he said, ‘That’s how the story goes but it can never be proved because the Special Branch files were destroyed in 1989.’

‘Convenient.’ I said, ‘So where did you have the reception?’, ‘Fraser Conserdyne booked the BLF hall in Ann St. There were about a hundred people there. Our friends, Pauline’s family, and of course a lot of Party well-wishers.’, ‘And a least one or two spies for ASIO and the Special Branch.’ ‘Of course, you couldn’t keep them away. They would have been like flies around a honey pot. Who they were we didn’t know or care. Surveillance was a fact of life and nobody worried about it. Jim Eustace was there.’

I had seen photos taken at the reception. They showed a happy convivial occasion. Apart from Alan’s friends in the Eureka Youth League there were a number of older comrades because they were proud of Alan. Just after arriving in Brisbane he found himself on the State Executive of the Communist Party – and the state executive of the Plumbers Union. If only there were more like him in the Party. One of the photos was of Alan and Pauline chatting with Jim. It was a picture devoid of any suggestion of treachery or malice. Jim looked like an ordinary young man, fair with short hair and a beard. The beard was the only feature that distinguished him – as though if he shaved it off he would disappear into thin air.

Beards weren’t popular amongst radical youth at that time like it was in the early sixties. That’s when I went overseas. I knew some of the Eureka Youth League members. They were mostly children of communists and knew from personal experience what it was to be outcasts and outsiders. Perhaps that is why they affected a sceptical attitude to the society at large and duffel coats and beards were popular. The beatniks made outsiders, not so much respectable, but accepted. When I returned to Australia in ’67 the youth revolt was in full swing, the whole youth scene had changed. But Jim Eustace somehow did not fit in.

On a later occasion, many years later, Alan showed me a copy of an ASIO report, once secret of course. It read like an account of some family gathering reported in the local suburban newspaper. As a document it was much like typewriter documents of the period but without mistakes. Yet it had sinister aura about it. The grammar was correct: under the heading of Attendance the reader was informed that, ‘About 100 persons attended the function amongst whom were the following:’ Amongst whom! Such pedantic language used for such a scabrous purpose somehow offended me, as if using it for such a purpose demeaned our language. Not all attendees’ name were there but of those that were, their names were in full and they were accompanied by their ASIO file number. Jim’s name was there: James Eustace QPF.11036.

‘I knew Jim Eustace,’ I said to Alan. ‘I met him some time after the wedding. He was in my Communist Party branch. He was a quiet reserved sort of bloke, didn’t have much to say for himself. He seemed painfully shy and people felt sorry for him. Charlie Gifford asked me to visit him and engage with him.’ So I told Alan of how I went to his humble little flat in Albion. It was part of an enclosed veranda of an old Queenslander. He seemed nonplussed to see me but he invited me in and offered me a cup of tea. He had the insides of a radio dismantled on the kitchen table. He said that fixing radios was his hobby. I congratulated him on being clever enough to do that sort of thing but he didn’t respond to my flattery.

I am not a good conversationalist but I can usually get a dialogue going by asking about the other person’s life. But this didn’t work. He seemed to be a man without a past, without a family, without ambition. When I tried to talk politics I chose as a topic the dispute between the USSR and China. This was a favourite topic of conversation between communists at that time but he didn’t seem to have any clues. The conversation was one sided and it kept petering out into silence. I gave up.

‘Yes, poor old Jim,’ Alan said. ‘You know the story?’, ‘No, tell me.’ I had heard gossip but I looked forward to hearing what Alan knew. ‘Well there was something funny about Jim. He was always asking stupid questions.’ ‘Like what?’ ‘As an example, ‘How many of us are there?’. Because everything was open and above board he would know the answer to that anyway. So why ask me? Questions like that which had no bearing on anything we were doing.’

‘Suspicious.’ ‘That’s right. So I went and visited Sonny Miles. I said, ‘Sonny, we’ve got this bloke in the League who’s always asking stupid bloody questions. I reckon he must be a plant of some kind.’ I asked Sonny what I should do.’

‘What did he reckon?’ ‘He said, ‘don’t worry about it Mate. Just give him plenty of work to do. Doing paste-ups, selling the paper – that sort of thing. Put the bite on him all the time. People like that are really useful.’

‘So, no worries?’ I asked. ‘No, but he was always hanging about our place. Of course everyone else did too. I don’t know how Pauline put up with it. But Jim always seemed to be there. As if he adopted us as his family. Because he always tried to be congenial — in his own dopey way — and helpful I found it hard to piss him off. Like a dog without a home that comes in off the street and you know it would be heartless to kick him out.’

‘But that situation could not continue?’ ‘That’s right. But one day he came up to me and said, ‘Alan, There’s something I have to tell you.’ I sensed that what he had to tell me was important so I was all ears.’ ‘Alan,’ he said, ‘Since I’ve joined the EYL I’ve come to realise what nice decent people you are.’ ‘That’s nice Jim, and…?’

‘I’ve been a spy all this time. I’m very sorry. I can’t say anything else except you’ll never see me again.’ Alan and I thought about this for a while. ‘That’s a good story Alan, I suppose no one ever did see him again.’ ‘No, and I often wonder what happened to him. And I wonder if he really was an undercover plant for ASIO or Special Branch.’ ‘I know what you mean Alan,’ I said. ‘You would expect that an agent would have more finesse than what he had. Perhaps he was living in a kind of fantasy world and it was all in his imagination. Jim Eustace, intrepid undercover operative – that sort of thing.’

‘A Walter Mitty character? I’ve often wondered about that. But the point is we never saw him again. Pauline was pleased about that.’

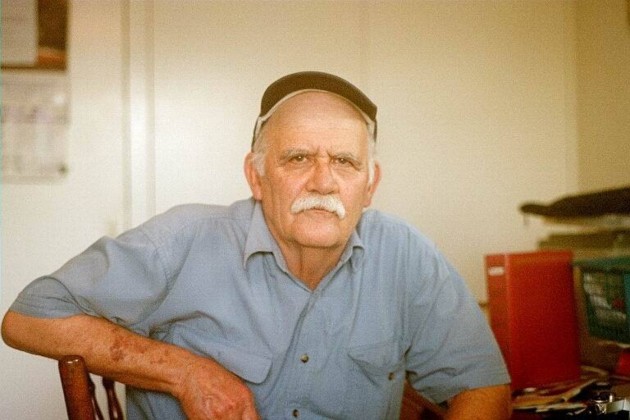

Ross Gwyther: Ted Riethmuller was born in Kingaroy. The year was 1939 and so he was an observer of the tumultuous events that shaped the second part of the 20th Century. He served his time as an electrician in Bundaberg and Brisbane. During his apprenticeship he joined the ETU and became interested in politics. In the early sixties, like many other young Australians he travelled to the UK and it was there that the class nature of society could not be ignored and it hastened his move to the left. Although the radicalism of his youth was tempered by age and experience and until his passing in 2019, he always embraced the ideals of universal peace, fraternity and the emancipation of the down trodden.

His interest in social history and labour history came with a strong belief that the experiences of the common people deserve to be documented. In particular he wanted to see the struggles and sacrifices of activists of the past acknowledged, honoured and their successes and failures learned from. He was always optimistic about the future but agreed that such hope is hard to justify. In his retirement, Ted wrote a collection of Workplace Sketches as an exercise in autobiography and a contribution to social and workplace history – and he encouraged others to do the same. The Brisbane Labour History Association has published a number of these sketches in our biannual journal, and are working together with Ted’s son Max to publish all of this work in a single volume later this year. This piece will be published in the next edition of the Queensland Journal of Labour History.

Radical Currents, Labour Histories, No. 1 Autumn 2022, 45-47.