Warwick Eather and Drew Cottle

Unskilled workers in rural New South Wales and Victoria formed a number of unions in the first decade after federation. By mid-1910 these unions had amalgamated to form the Rural Workers’ Union. Three years later the union was absorbed by the Australian Workers’ Union. Commencing in late 1909 the unions compiled logs of claims for improved wages and conditions, and commenced industrial campaigns in support of their claims. Their strike action alarmed farmers in NSW and Victoria. In response, the NSW based Farmers and Settlers’ Association, in early 1914, assembled 3,000 farmers to break strikes and threatened to use them prior the outbreak of war. During the early war years NSW and Victorian farmers continually broke strikes in the bush waged by wheatlumpers, members of the RWU/AWU. Farmers became experienced strikebreakers. They mobilised en masse in August 1917 and broke the General Strike.

On 24 August 1917, day 22 of the General Strike, The Land reported that the ‘country strike breaking movement has been recognised as the most important development of the crises’, the men ‘as strikebreakers … stand in a class of their own’ and they ‘are the only invincible power which stands between this State [New South Wales (NSW)] and a reign of anarchy and tyranny’. Nearly 3,000 men, mostly farmers, were camped at the Sydney Cricket Ground. Their spirit was ‘likened to the spirit which has impelled the best of the manhood of this country to gallantly face their Empire duties in the field of battle’. In Sydney the battle fronts were the waterfront, abattoirs and gas works, and on the streets.[1]

The Land correctly argued that the arrival of thousands of bush volunteers was ‘the most important development of the crisis’. Without these volunteers the strike would not have been defeated, even with the large amount of ‘coal on grass’, a view accepted at the time by union officials and leaders of business and farming peak bodies, as well as one early historian of the strike. The strikebreakers enabled the NSW government to rebuff every attempt to mediate the dispute, which eventually forced the Strike Defence Committee to direct striking workers to return to work on the government’s terms.[2]

This paper analyses how and why farmers in NSW and Victoria became strikebreakers. Our focus is on the conservative rural mobilisation before and during the First World War. By early 1914, the NSW based Farmers and Settlers’ Association (FSA) had over 3,000 farmers willing to break strikes. Mobilised as localised groups before the war, they were never deployed en masse until August 1917. During 1914, the Victorian Farmers’ Union formed a provisional executive and established branches. Victorian farmers became as active as their NSW counterparts and were prepared to break strikes in Melbourne. During 1916-17 farmers from both states broke strikes called by wheatlumper members of the Rural Workers’ Union (RWU)/Australian Workers’ Union (AWU). By August 1917 farmers were experienced strikebreakers.

Scholarship on farmers and their peak organisations in NSW and Victoria ignore this rural mobilisation. William Bayley’s history of the FSA concentrates on organisational purpose, membership and branch matters, wheat sales and political representation.[3] Histories of the wheat industry examine land settlement, markets, prices and wheat types.[4] Studies on the Australian Country Party focus on its formation, electoral success and early leaders.[5] Work on the wool industry and land and finance companies never discuss the farmers’ industrial campaigns.[6] Ernest Scott’s history of the home front during the war offers an account of trade agreements, shipping shortages, wheat stockpiles, mice plagues and industrial strife.[7]

The conservative rural mobilisation before and during the war is an early manifestation of the fear that drove the formation and growth post-war of a host of right-wing organisations. Many of these organised in secret and were active until the late 1940s. In his study of the secretive, para-military Old Guard, Andrew Moore argued that the recruitment of strikebreakers in 1917 represented capital’s fears about Labor governments and ‘alliances between … the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the Sinn Fein and an untrustworthy working class’. Leaders and members of the Old Guard in the 1930s were prominent in breaking the General Strike, and ‘the “farmers’ army” … was a working model for developing counterrevolutionary preparations’.[8] The Old Guard was not the sole organisation that readied itself to protect the state from the ravages of the Labor Party, trade unions and communists. The Producers’ Advisory Council, the New Guard and the Riverina Movement in NSW and the White Army, the League of National Security and The Association in Victoria were also active, with farmers as members and leaders.[9]

The history of labour during the first decades of the twentieth century is well documented.[10] However, industrial campaigns waged by wheatlumpers have never been studied. Vere Gordon Childe in 1923 and Mark Hearn and Harry Knowles in 1996 outlined how the RWU amalgamated with the AWU during 1912-13.[11] Our work on the rabbit industry highlighted how the industry helped wheatlumpers achieve higher daily rates of pay in the period to 1920.[12] The conservative rural mobilisation cannot be understood without analysis of the wheatlumpers’ industrial campaigns. This paper also focuses on wheatlumpers, a forgotten group of workers. It examines how the RWU was formed and its amalgamation with the AWU, their logs of claims and how farmers in NSW and Victoria responded to these claims. Their responses are central to why they became experienced strikebreakers.

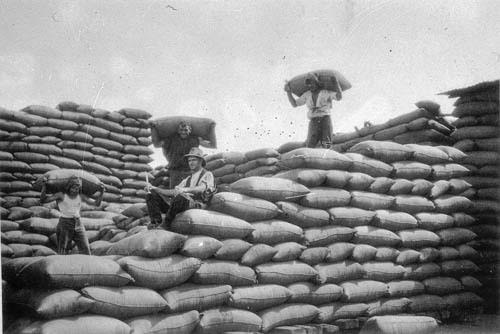

Wheat lumpers stacking wheat, Tullamore, NSW, 1933-34

Source: State Library of NSW Image no. bcp_04869h

The General Strike and the two competing theories about its causes are not central to this paper. They have been analysed by Childe, Coward, Bollard, Jurkiewicz, Turner, Burgmann, Taksa, Tierney, Kimber, Fahey and Lack, and a series of articles in The Hummer.[13] Two sections of this research relate to use of farmers as strikebreakers. Bollard argued that a government-employer conspiracy ‘is much more plausible … because of the rapidity with which the State mobilised, particularly with regard the recruiting and directing of volunteer effort’.[14] Coward, Bollard and Jurkeiwicz found there was no conspiracy between employers and the NSW government.[15] These conclusions represent a misunderstanding of the operations of capitalist power. In 1976, Humphrey McQueen argued that ‘capitalist power was not based on some vast, over arching conspiracy’. Instead it is how leading capitalists, conservative politicians, judges and senior public servants knew each other, socialised in the same clubs, moved in the same social circles or met each other in the routine of their ‘normal business of running the country’.[16] Our research on the BHP group of companies during World War Two, and the Sydney rich, the private banks and capital in the 1930s and 1940s reinforce McQueen’s argument. It explains why farmers mobilised quickly to break the strike in Sydney and why many employers applied to deregister unions and blacklist militants during and after the general strike.[17]

The strikebreakers are rarely mentioned in the dispute’s historiography. They were recruited, camped at the Sydney Cricket Ground and other locations, were given every assistance, food and beer, their illnesses (everything from colds to venereal disease) and injuries were treated at the government’s expense, and they were employed on a variety of work.[18] J.B. Holme’s official account of the strike explains that the strikebreakers came from the bush because their loyalty was confirmed by local elites, they had little involvement with unions and, when encamped, were isolated from the influence of city based unions and strikers. Holme’s description of the volunteers’ recruitment ignores the strikebreaking role played by farmers before August 1917.[19] Ian Turner believed that rural labour was selected because the IWW had less influence in the bush, a claim that Verity Burgmann and Rowan Day and Drew Cottle question. Day and Cottle explained that there were more IWW members and supporters in the bush than in the cities.[20] Most studies highlight how the FSA and Primary Producers’ Union (PPU) recruited strikebreakers, but this assistance came later than other initiatives and was not the only channel used to get labour.[21]

Farmers and Wheatlumpers

In NSW, a group of farm labourers, fed up with poor rates of pay, extremely long working hours and the lack of award coverage, met in Germanton (now Holbrook) in November 1907 and formed the Australian Farm and Bushworkers’ Union. They established headquarters in Albury and appointed a full-time organiser. By early January 1908 branches were formed in Henty, Culcairn, Corowa, Wagga Wagga, Narrandera and Hay, with around 300 members. Two months later the AWU and the Australian Farm and Bushworkers Union met in Wagga Wagga, dissolved the Bushworkers Union and formed the RWU. The new union established its headquarters in Wagga Wagga.[22] During the first decade after federation Victorian farm labourers and other bush workers joined several small unions – the Mildura Workers’ Union, the Donald Workers’ Union, the General Workers’ Union (Castlemaine and Maryborough), the Firewood, Coal, Hay and Corn Trade Union, the Gardeners and Nurseymen’s Union and the Dandenong Rural Workers’ Union. These unions amalgamated on 16 October 1909 to form the Rural and General Workers’ Federation of Victoria, which eight months later became the Victorian branch of the RWU.[23] On 21 November 1910, delegates from NSW, Victoria and South Australia met at Melbourne’s Trades Hall, adopted a constitution for a federal organisation and registered it with the Commonwealth Arbitration Court. The NSW and Victorian branches held their first Annual General Meetings in September 1911 and thereafter the union sought amalgamation with the AWU. AWU leaders wanted all bush workers as members to increase the union’s industrial and political power. Many bush workers were members of up to four unions because of the seasonal nature of work in the bush outside the rabbit industry. The majority voted for amalgamation and the enlarged AWU emerged in early 1913.[24]

Wheatlumpers joined the RWU/AWU and around 10,000 men worked in this very seasonal occupation. Harvested wheat was placed in three-bushel jute bags that weighed 180 pounds when full. The harvest occurred in a short period with 52 per cent of the total output delivered to railway sidings at one time. The railways couldn’t move the grain as fast as it arrived so it was stacked at sidings.[25] Stack dimensions usually started 15 feet from the railway line and extended back 40 feet. The length of the face parallel to the railway and the stack’s height varied. Wheatlumpers lumped bags from the farmers’ vehicles to the stack. When railway trucks were available the workers lumped from the stacks into the trucks. This procedure was repeated twice at the port. Justice Heydon, of the NSW Court of Industrial Arbitration, found that individual workers lumped 500 bags a day and walked at least 6.5 miles at around 2 miles an hour. Gun wheatlumpers, however, lumped between 1,800 and 2,200 bags a day. Forms of payment varied. Men could be paid per bag (generally 3 farthings [0.75d]), or an amount per hundred bags, or a daily rate. Piece rates returned higher pay (some workers earned £15 a week in the early 1910s) but the work day was subject to many disruptions that impacted earnings. The unions and workers preferred day rates because it guaranteed wages despite weather conditions or output.[26]

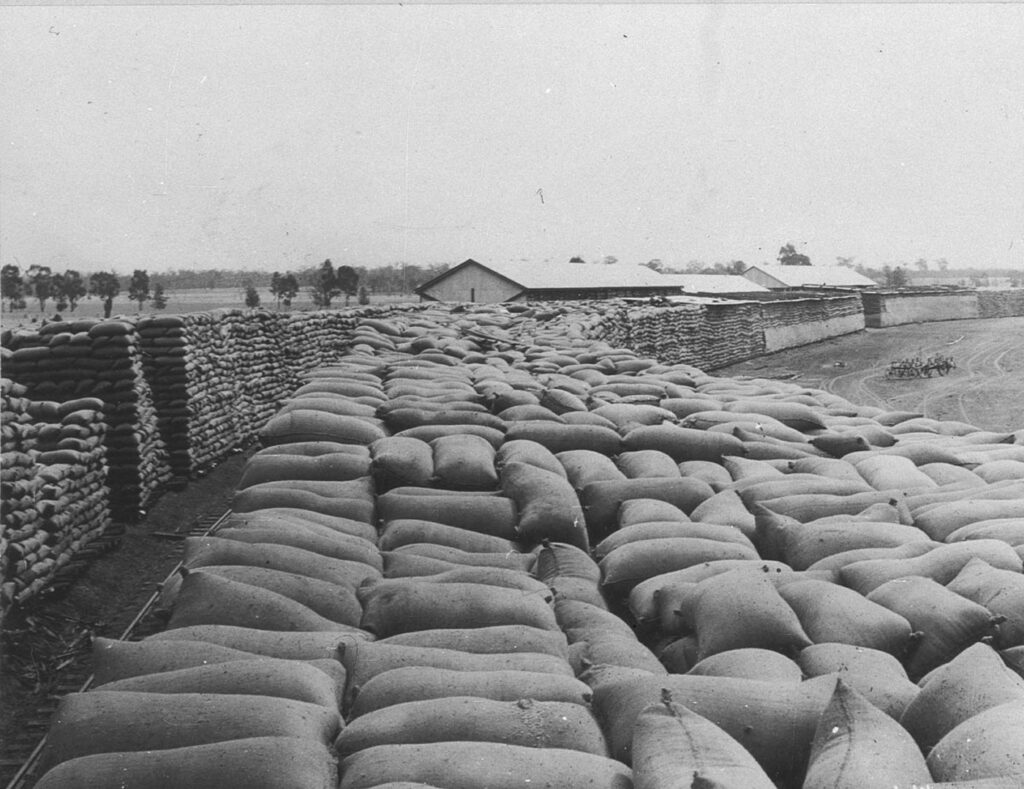

Wheat in Bags by Railway, 1915 and 16 Stacks, Quandary, NSW, 1916.

Source: State Library of NSW Image no. bcp_02982h

The RWU and its predecessors prepared logs of claims from late 1909. They sought a 48-hour work week over five and one-half days, daily pay rates, overtime payments for night work, double time on Sundays and public holidays, no child labour under 15 years of age, and union preference. Wheatlumpers wanted 12s a day in 1910 and 16s a day in 1914. Along with the country press across NSW and Victoria, farmers opposed the logs claiming the pay rates were too high, the total hours of work too low and the restriction of child labour unworkable. Wages paid to wheatlumpers lagged behind rates listed in the logs before 1917. Most wheatlumpers received 10s to 14s a day, and some achieved 16s a day. Piece rates of 5s to 6s a hundred bags were standard, while some gained 6s 6d a hundred.[27]

NSW’s industrial laws excluded general farm hands. On 8 December 1911, an RWU application to the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration for a compulsory conference was rejected by Justice Higgins because the FSA argued that there was no dispute.[28] Delegates to the July 1912 FSA Annual Conference, inspired by Queensland Farmers’ Union members who broke the Brisbane General Strike and South Australian farmers’ action against a fertiliser workers’ strike in Adelaide, resolved to break any strike that disrupted the transport and delivery of farm and dairy produce.[29]

While strikes in Sydney threatened farm income, the ongoing conflicts with the RWU and AWU made farmers experienced strikebreakers. In 1913 the AWU engineered an industrial dispute at Narromine in NSW to gain access to the federal court. This failed as the FSA refused to recognise that a dispute existed, with Narromine farmers and non-unionists completing the harvest without union labour.[30] Other AWU attempts to enforce its log occurred in the Riverina and in northern Victoria from late 1913. Clashes between strikers and farmers, vignerons and their non-union employees turned violent. The FSA’s Wagga Wagga branch wanted special constables to protect farmers and non-unionists, while vignerons around Rutherglen formed a 100-strong mounted force for protection.[31]

These industrial disputes occurred while a major anti-union action unfolded in New Zealand. During October and November 1913, the Employers’ Federation, the Farmers’ Union and the Associated Farmers’ Society broke a series of strikes across the country. Farmers were enrolled as special constables and restored ‘law and order’ in Auckland, Wellington, Dunedin, Christchurch and other centres, sometimes violently. The New Zealand farmers’ successes inspired Australian farmers to take similar action against unions: ‘What the farmers of New Zealand did the farmers of Australia can do, given an equal opportunity’.[32]

In late 1913 the AWU declared black farm produce harvested in the Riverina by non-union labour and the ban was endorsed by other unions. The FSA and the NSW Employers’ Federation met in early January 1914 to respond to repeated stoppages by unions. While they favoured following the New Zealand example, appointing farmers as special constables was not possible under a Labor government. Instead, the FSA compiled a list of farmers prepared to break strikes disrupting the harvesting and transportation of farm produce. All 430 branches were asked for names of six members who would travel to Sydney ‘to load and unload farmers’ produce’ during a strike. Strikebreakers’ railway fares and work would be paid, the latter at union rates. By February the FSA had over 3,000 names, with over 400 from the Wagga Wagga area. FSA branch meetings announced this 3,000-strong strikebreaking force and reports were published in country newspapers.[33]

The FSA was determined to use this force. On 14 January Sydney wharf labourers declared they would not handle black wheat. The FSA threatened to have its members load the produce and break the ban. Wharf labourers continued to load wheat as it was difficult to determine if it was black.[34] Meanwhile, wheatlumpers across the Riverina struck work when agents employed non-unionists and Thomas Campbell, the FSA general secretary, reported that ‘their places were taken by the farmers themselves’.[35] While the battles with the AWU were ongoing, the FSA promised to send 5,000 strikebreakers to Sydney to help break a meat strike during February and March 1914. The strike ended before the farmers mobilised.[36] In April 1914 Sydney trolley and draymen declared black chaff harvested in the Riverina and supplies banked up at the Redfern railway station. The FSA telegraphed branches for volunteers to move the chaff. Within 48 hours over 100 men, 50 from Wagga Wagga, were in Sydney ready to break the black ban, and more were in transit. Before they acted the Premier, William Holman, brokered a settlement, promising to include the AWU in the Arbitration Act ‘so that rural workers might have their claims heard’. The trolley and draymen lifted their ban, but the FSA opposed rural workers having access to arbitration. The FSA lauded the farmers’ arrival in Sydney, warning ‘they will be prepared, and hundreds more if necessary, to answer a similar call at any time’.[37] For The Pastoral Review, they were an army of producers ready to fight industrial labour: ‘the producer should realise it is now war to the knife between him and the union agitator. Either one or the other must triumph, because their aims and objects are directly opposed’.[38]

Unlike their NSW counterparts, farmers in Victoria had little to offer because they were not as organised; early in 1914 the Victorian Farmers’ Union had a provisional executive and branches were being formed throughout the year.[39]

Capital’s Fears

While possible industrial confrontation ceased with the onset of war in August 1914, fears of further industrial struggle haunted capitalist leaders during the next three years. This fear intensified with increasing numbers of industrial disputes. In NSW spiralling inflation and slow wage growth led workers to take direct action; from October 1914 to the end of 1916 there were 543 strikes in NSW. Striking workers were condemned as being disloyal and unpatriotic by conservative politicians, businessmen and many arbitration judges.[40] In response capitalists organised to protect themselves, although differences about the level of threat and nature of any response existed between and within various sections of capital. Employers in NSW formed the Traders’ Defence Association in May 1916, while the National Union, a ‘substantial organisation of business interests, both town and country’ formed branches in Sydney (mid-1916), Melbourne (February 1917) and Brisbane (mid-1917).[41] By October 1916, John Ritchie, President of the Pastoralists’ Association of Victoria, warned of ‘the threatening danger of an industrial upheaval in the Commonwealth being precipitated by an active and noisy minority of extremists among unionists’.[42] In November, William Brooks, Chairman of the Employers’ Federation of NSW, echoed these views at the Federation’s Annual Meeting declaring that union officials planned ‘to set up a form of dictatorship, defying the law and placing their own demands above the safety and welfare of hundreds and thousands of men, women and children’.[43] The Pastoral Review urged capital and government to ‘end mob rule’and advocated class warfare to end union tyranny:

Why is Australia in this condition? Simply and solely because employers have been too selfish to combine and again because those who have put a fight are too mealy mouthed to take off the gloves …. The breaking point is near, and the sooner those who wish prosperity to their country combine and fight for it the better for all concerned. The trouble will be short and sharp when it comes, but as far as socialistic legislation and militant unionism are concerned, the writing on the wall can be read by those who are not blind.[44]

From mid-1916 there was a widespread belief in business, conservative political and legal circles, that a general strike was imminent. William Morris Hughes, the Prime Minister in a divided Labor government, believed that a general strike was coming and his government ‘may be compelled to take serious measures to deal’ with union militancy.[45] In March 1917, The Pastoral Review urged all employers to confront the ‘unlawful terrorism of the unions’ and the use of a general strike.[46] Herbert Brookes, the newly-elected president, told delegates attending the Associated Chambers of Manufacturers of Australia’s May 1917 annual conference that employers must use a lockout of ‘a general character’ against a general strike. He believed an industrial upheaval of very serious proportions was imminent as disloyalists strove to disrupt supplies for the allies fighting the war, but believed manufacturers would see the ‘matter through to the bitter end’.[47] In July 1917, Arthur King Trethowan, FSA President, told delegates attending the annual conference ‘that a trial of strength between unionism and the National [sic] government would be forced by militant Labour leaders’. He declared that the leadership ‘had taken measures whereby their people were easily get-at-able [sic] and well organised for free labour in both country and city, if need be’.[48] The day after Trethowan’s warning the Sydney Morning Herald reported that ‘A general strike directly will be upon us, if the signs are being read aright’. George Fuller, the Acting NSW Premier, was quoted in the report as saying that stoppages of work were

being engineered by men who want to keep up the industrial ferment … It is appalling that … we have to face constant stoppages of work in different industries arising from the actions of men who seem determined to bring about a serious industrial crisis.[49]

Strikebreaking Farmers

During 1914-17, wheat farmers increased production in response to the federal government’s ‘grow more wheat’ campaign. National output increased from 24,892,000 bushels of wheat in 1914-15 to 179,066,000 bushels in 1915-16 before declining to 152,420,000 bushels in 1916-17. Most of the harvest was sold to the British government but there were no ships to transport it. Bagged wheat was stockpiled. Victoria had 5,159,561 bags of the 1916-17 crop and 6,217,406 bags of the 1917-18 crop in stacks as at 30 June 1919. The number of bags stored in NSW in mid-July 1917 was 11,377,447, of which 8,182,622 were stacked at country railway stations.[50]

The 1915-16 wheat harvest in Victoria was disrupted by industrial disputes. At Nurmurkah, in the Goulburn Valley, wheatlumpers in early January 1916 demanded 16s a day and went on strike when their demand was not met. Local farmers stacked the wheat and broke the strike.[51] In Melbourne the same month, wheatlumpers at Williamstown struck work demanding a pay rise and better overtime payments. They declared the wheat black. Frederick Hagelthorn, the Liberal government’s Minister for Agriculture and Victorian Wheat Commissioner, telegraphed all Victorian agricultural societies and farmers’ organisations seeking farmers to break the strike. The New Zealand experience of 1913 and the FSA plan of industrial confrontation in NSW were to be put into action. Nearly 1,000 farmers volunteered, but they were not needed; Billy Hughes negotiated a settlement that satisfied the strikers. Hagelthorn instructed the proposed strikebreakers to ‘keep in readiness for any possibilities that may occur’.[52]

In mid-June 1916, Victorian mill carters and storemen, members of the Flour Mills Employees’ Union, stopped work to support striking members of the Operative Bakers’ Society who were demanding day baking. The dispute disrupted flour and bread production. On 16 June the Victorian Liberal government sought farmers to act as strikebreakers and authorised payment of award wages and free rail passes. The farmers were not mobilised as the government decided against seizing the mills and strikers returned to work on pre-strike conditions in early July.[53]

In NSW, wheatlumpers employed at Old Junee receiving station were paid 6s 6d per hundred bags. In January 1917 they demanded an extra 6d because they had to lay dunnage (loose material spread on the ground on which the stack was built). The wheat commission’s agent refused and a strike commenced. Strikebreakers who arrived by train from Sydney refused to work after talking with the strikers. Local farmers stacked the wheat and broke the strike.[54]

Stacked wheat was exposed to damage over an extended period of time from weather and pests. The latter, especially mice and weevils, caused the heaviest losses. In 1917 Australia suffered the worst mice plague of the twentieth century. Mice first appeared in NSW during December 1916. By June 1917 they were in plague proportions across the south-east states. Although the plague was widespread, Henty, Holbrook, Old Junee, Wagga Wagga and hilly areas around Grenfell, Greenthorpe, Molong and Parkes were spared. The rest of the south east suffered total devastation.[55]

During the first half of 1917 the AWU campaigned for 20s a day for wheatlumpers. Union organisers travelled to stacking sites encouraging members to demand the sum. Disputes erupted throughout the wheat belt: at Goulburn, The Rock, Old Junee, Ganmain, Boree Creek, Lockhart, Temora, Narrandera and West Wyalong in NSW, and at Maffra, Warracknabeel, Beulah, Horsham, Ultima, Geelong, Charlton, Watchupga, Sheep Hills, Nullan, Minyip, Rainbow, Horsham, Jung, Wedderburn, Dimboola, Murrayville and Elmore in Victoria. Wherever possible farmers replaced strikers.[56] Given this union threat to the wheat, George Beeby, the NSW Minister for Labour and Industry, referred the issue to the Court of Industrial Arbitration. On 30 May 1917 Justice Heydon granted wheatlumpers 20s a day or 8s a hundred bags until 24 July 1917, a decision that horrified farming organisations.[57] The AWU’s attempts to have the Heydon award applied in Victoria were rebuffed by Frederick Hagelthorn, the Minister of Agriculture. Nevertheless, some Victorian lumpers gained 20s a day through direct action.[58] The NSW government requested the court fix a permanent award and on 4 September 1917 Heydon set rates of 15s a day or 6s a hundred bags until to 18 October 1918.[59]

500,000 mice – 8 tons – 4 nights catch, May 1917 at Lascelles (Vic.) trapped by double-fencing system

Source: State Library of Victoria Picture: F.G. England

At the height of the 20s a day campaign, Hagelthorn declared that ‘in future no strikes by the men who are handling the wheat at country stations are to be tolerated by the Victorian Wheat Commission’. Hagelthorn met with buying agents to draft a schedule of rates for the stations. If the rates were refused Hagelthorn declared wheatlumpers would be replaced by volunteers from the bush, ‘many of whom have announced their willingness to undertake the work’.[60]

On 12 June 1917 the NSW Wheat Board considered how to deal with stacks that the mice had destroyed. Enlistments and the rabbit industry had eliminated the reserve army of labour in the bush, the urban unemployed refused work re-bagging wheat at 20s a day, and the wheatlumpers’ industrial campaigns made finding workers difficult.[61] The Board decided to pay local farmers award rates to re-bag the wheat and re-condition the stacks. Farmers moved onto the damaged stacks by the end of June. At Marrer, north of Wagga Wagga, 50 farmers, all members of the local FSA branch, commenced re-bagging the wheat in early July. AWU members in the yard asked the farmers to take out union tickets. When the farmers refused the men asked the local agent to sack the farmers. When he didn’t the unionists went on strike. Farmers broke the strike and earned 20s a day doing so. The confrontation at Marrer was repeated at stacks across the NSW wheat belt.[62]

Wheat Stacks in a Railway Yard. Lumpers Seated.Source: State Library of NSW

Six weeks later, on 2 August, craftsmen employed in the NSW Railways and Tramways Department went on strike in protest against the introduction of job cards. The strike rapidly spread to other industries and interstate, with a total of 100,000 workers joining the strike. It lasted for 82 days, ending on 22 October, with some workers striking for a couple of days while others struck for the duration. On 6 August 1917 the NSW government gave striking workers until 10 August to return to work or they would be dismissed and replaced, and Nationalist parliamentarians representing country constituencies telegraphed shire and municipal councils, FSA and PPU branches, and progress associations in their electorates. The telegraphed message was, ‘Glad if you will organise volunteers for positions as drivers, slaughtermen and handymen. Accommodation provided. Fares paid. Inform me of number of men and class of labour. To be called upon when required’. Award wages would be paid.[63] The FSA and PPU offered to recruit strikebreakers on 7 August and six days later, Beeby urged them to ‘get men down to the city’. All branches were telegraphed the same day.[64] J.B. Holme, the under-secretary in the Department of Labour and Industry, and a country based railway inspector also actively sought strikebreakers.[65] The government and Nationalist parliamentarians again contacted local councils and requested more volunteers throughout the first month of the stoppage.[66]

The parliamentarians’ initial appeal led mayors and shire presidents to hold public meetings in at least 65 towns to recruit strikebreakers. There were few unemployed in the bush. Trethowan believed the strike began at a time when, ‘There is nothing much for us [the farmers] to do now before shearing … we can leave [the] farm for a considerable time’.[67] PPU members from Scone and the Illawarra arrived in Sydney on 7 August and 7,363 strikebreakers were registered over the duration of the strike.[68] The majority came from towns and villages in the Riverina where George Beeby, the member for Wagga Wagga, had close links with the FSA. Further strikebreakers came from Armidale, Quirindi, Parkes, Wellington, Narromine, Inverell, Orange, Scone, Gloucester, Denman and other centres. Very few were from railway towns or inland mining areas. Most were farmers, while lawyers, dentists, bank clerks, businessmen, ‘skilled mechanics’, tradesmen, drovers, farm hands, shire councilors, council engineers, timber-cutters, ‘storehands’, and stock and station agents became strikebreakers. Wagga Wagga sent 138 men, of which the majority were farmers but there was also a blacksmith, a bricklayer, a motor mechanic, a shearer, a carrier, a stock and station agent, a shop assistant, a railway inspector, a saw miller and a wool classer.[69] While the motives of the farmers are clear, the motivations of other volunteers can only be speculated. Supporting the war effort and protecting the conservative NSW government would have been central concerns. The inclusion of tradesmen and other manual workers, who could join trade unions, indicates the conservative nature of many rural workers and the conflict over conscription that divided families and split many rural communities during 1916-17.[70]

Large numbers of Victorian farmers were ready to break strikes in Melbourne if workers went out in support of the Sydney strikers. They were not mobilised as the Victorian government and Melbourne employers secured sufficient strikebreakers through the Federal government’s National Service Bureau located in Collins Street.[71]

Conclusion

NSW farmers broke the 1917 General Strike in Sydney and Victorian farmers stood ready to do the same in Melbourne. This conservative rural mobilisation was the outcome of localised events that started years earlier. In 1912, FSA members wanted to imitate farmers in Queensland and South Australia who broke strikes. The next year farmers in New Zealand broke a series of strikes across the country, which further inspired farmers in NSW and Victoria. In early 1914, the FSA assembled a 3,000-strong force of farmers willing to break strikes in NSW that disrupted the harvesting and transport of farm produce. FSA leaders threatened to use this force during 1914 to break strikes and black bans in Sydney, and mobilised a small group in April 1914. Only the onset of war prevented its mass mobilisation.

While industrial disputes in Sydney and Melbourne were troubling, farmers faced more immediate pressing problems. RWU/AWU inspired industrial confrontation, based on union claims for improved wages, conditions and hours of work, confronted farmers on a regular basis. The industrial campaigns of wheatlumpers during 1916-17, the inability to move millions of bags of wheat from country areas during the war, and the threat to this stockpiled wheat from mice and weevils, forced farmers to become efficient strike breakers.

Capital, government and the judiciary viewed working-class militancy as unpatriotic and disloyal. Following a wave of industrial disputes during 1915-16 they feared a large industrial upheaval. The strike in the NSW railway workshops and its spread to other industries was the big dispute capital expected. The Nationalist government’s response was decisive and effective. Strikebreaking replaced negotiation and compromise. When the General Strike started the farmers were ready and experienced: ‘as strikebreakers’ they stood ‘in a class of their own’.

Warwick Eather is an independent scholar who lives in Melbourne. With Drew Cottle he is writing a history of the rabbit industry in south-eastern Australia. His other research interests include bush unionism and work of wheatlumpers and night soil carters.

Drew Cottle teaches History and Politics at the University of Western Sydney.

Endnotes

[1] Land, 24 August 1917, 8 and 12. V. G. Childe, How Labour Governs: A Study of Workers’ Representation in Australia (London: Labour Publishing Company Limited, 1923), 84.

[2] Robert Bollard, “’The Active Chorus’: The Mass Strike of 1917 in Eastern Australia” (PhD diss., Victoria University, 2007), 8. Robert Bollard, In The Shadow of Gallipoli (Sydney: Newsouth Publishing, 2013), 126 wrote that the claim was an afterthought of the officials, given as a reason for ending the strike. The Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), 25 August 1917, 7 reported, ‘New Zealand, in 1913, was rescued from tyranny by free men from the country, just as New South Wales is being saved today. There is a remarkable similarity in the origin, development and treatment of the two great strikes’.

[3] William Bayley, History of the Farmers and Settlers’ Association of New South Wales (Sydney: The Association, 1957).

[4] A.R. Callaghan and A.J. Millington, The Wheat Industry in Australia (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1956); Egdars Dunsdorfs, The Australian Wheat Growing Industry, 1788-1948 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press (MUP), 1956).

[5] Don Aitken, The Country Party in New South Wales (Canberra: Australian National University (ANU) Press, 1972); B.D. Graham, The Formation of the Australian Country Parties (Canberra: ANU Press, 1966).

[6] Kosmas Tsokhas, Markets, Money and Empire: The Political Economy of the Australian Wool Industry (Melbourne: MUP, 1990); J.D. Bailey, A Hundred Years Of Pastoral Banking: A History of the Australian Mercantile Land and Finance Company 1863-1963 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966).

[7] Ernest Scott, Australia During The War (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1940), 540-594.

[8] Andrew Moore, The Secret Army and the Premier: Conservative Paramilitary Organisations in New South Wales 1930-32 (Sydney: UNSW Press, 1989), 19-22.

[9] Ibid., chs 2-6; Andrew Moore, The Right Road: A History of Right-wing Politics in Australia (Melbourne: Oxford University Press (OUP), 1995), 23-66; Michael Cathcart, Defending The National Tuckshop: Australia’s secret army intrigue of 1931 (Ringwood: Penguin Books, 1988).

[10] Mark Hearn, Working Lives: A History of the Australian Railways Union (NSW Branch) (Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1990); John Merritt, The Making of the AWU (Melbourne: OUP, 1986); Robert Murray and Kate White, The Ironworkers: A History of the Federated Ironworkers’ Association of Australia (Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1982); Greg Patmore, Australian Labour History (Melbourne: Longman Cheshire, 1991); Bradley Bowden, Driving Force: The History of the Transport Workers’ Union of Australia 1883-1992 (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1993); Mark Hearn and Harry Knowles, One Big Union: A History of the Australian Workers Union 1886-1994 (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press (CUP), 1996); Mark Bray and Malcolm Rimmer, Delivering The Goods: A History of the NSW Transport Workers’ Union 1888-1986 (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1987), 63-64; Robin Gollan, The Coalminers of New South Wales: A History of the Union 1860-1960 (Melbourne: MUP/ANU, 1963), 152.

[11] Childe, How Labour Governs, 139-146; Hearn and Knowles, One Big Union, 112.

[12] Warwick Eather and Drew Cottle, ‘”As good as cash all the time”: Trapping rabbits in south-eastern Australia, 1870-1950’, Labour History, no. 111 (November 2016): 144.

[13] Bollard, ‘The Mass Strike of 1917’; Robert Bollard, “’The Active Chorus’: The Great Strike of 1917 in Victoria”, Labour History, no. 90 (May 2006): 77-94; Dan Coward, “Crime and Punishment: The Great Strike in New South Wales, August to October 1917”, in Strikes: Studies in Twentieth Century Australian Social History, eds. John Iremonger, John Merritt and Graeme Osborne (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1973), 51-80; W. Jurkiewicz, “Conspiracy aspects of the 1917 Strike” (Bachelor of Arts (Hons) Thesis, University of Wollongong, 1977); Ian Turner, Industrial Labour and Politics: The Dynamics of the Labour Movement in Eastern Australia 1900-1921 (Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1979), 108-159; Verity Burgmann, Revolutionary Industrial Unionism: The Industrial Workers of the World in Australia (Cambridge: CUP, 1995), 159-189; Charles Fahey and John Lack, “The Great Strike in 1917 in Victoria: Looking Fore and Aft, and from Below”, in Labour and the Great War: The Australian Working Class and the Making of Anzac, eds. Frank Bongiorno, Raelene Frances and Bruce Scates, Labour History, no. 106 (May 2014): 69-98; Lucy Taksa, “Defence not defiance: Social Protest and the NSW General Strike on 1917”, Labour History, no. 60 (May 1991): 16-33; Robert Tierney, “The New South Wales Railway Commissioners’ Strategic Pre-Planning for the Mass Strike of 1917”, Labour History, no. 98 (May 2010): 143-162; Julie Kimber, “Patriotism and its discontents: a small town in a great strike”, researchbank.swinburne.edu.au, accessed 1 April 2019; The Hummer, 12, no. 2 (2017).

[14] Bollard, “The Mass Strike of 1917”, 27.

[15] Coward, “Crime and Punishment”, 51-80; Bollard, “The Mass Strike of 1917”, 25-28; Jurkiewicz, “Conspiracy Aspects”, 56-64.

[16] Humphrey McQueen, “None dare call it conspiracy”, in Gallipoli to Petrov: Arguing with Australian History (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1984), 246-252.

[17] Warwick Eather, “The Trenches At Home: The Industrial Struggle in the Newcastle Iron and Steel Industry 1937-1947” (PhD diss., University of Sydney, 1986); Warwick Eather, ‘Throw Out The Socialists … We hold the destiny of this country in our hands’: The Australian Women’s Movement Against Socialisation in New South Wales 1947-1960 (Shanghai: Australian Centre For Labour and Capital Studies, 2012); Drew Cottle, Life can be oh so sweet on the sunny side of the street: A Study of the Rich of Woollahra during the Great Depression, 1928-1934 (London, Minerva Press, 1998); Warwick Eather and Drew Cottle, Fighting From The Shadows: The Private Trading Banks, Political Campaigns and Bank Nationalisation 1930-1949 (Shanghai: Australian Centre For Labour and Capital Studies, 2012).

[18] Turner, Industrial Labour and Politics, 151-152; Bray and Rimmer, Delivering the Goods, 63-64; Gollan, The Coalminers, 152.

[19] J. B. Holme, The Strike Crises, 1917 (Sydney: Government Printer, 1918), 50A- 57A.

[20] Turner, Industrial Labour and Politics, 151, Burgmann, Revolutionary Industrial Unionism, 160; Rowan Day and Drew Cottle, “Wobblies on the Wallaby”, Labour History, no. 109 (November 2015): 41-53.

[21] Turner, Industrial Labour and Politics, 151; Coward, “Crime and Punishment”, 57-58; Moore, The Secret Army, 20.

[22] Border Morning Mail (Albury), 9 December 1907, 3; Wagga Wagga Advertiser, 17 December 1907, 2 and 12 March 1908, 2; Worker (Wagga), 26 December 1907, 11.

[23] Worker (Wagga), 16 September 1909, 9; 21 October 1909, 19; 9 December 1909, 3; and 15 June 1910, 4; Rural Workers’ Gazette (RWG), December 1910, 1-2 and September 1911, 6-7.

[24] RWG, December 1910, 2 and September 1911, 6-7; Childe, How Labour Governs, 138-142.

[25] Dundorfs, Australian Wheat Growing, 221.

[26] [1917] Industrial Arbitration Reports, NSW (AR), 302-315; Farmer and Settler (F&S), 31 December 1909, 4; RWG, December 1910, 1-2. Lumping 2,000 bags a day at 0.75d a bag returned £6 5s 0d, an enormous sum that exceeded most male workers weekly wage.

[27] [1917] AR, 306; Royal Commission of Inquiry on Rural, Pastoral, Agricultural, and Dairying Interests (with particular reference to share-farming) (Sydney: Government Printer, 1917), LII, 14-15 and 293.

[28] Worker (Wagga), 12 July 1911, 2; Land, 6 February 1914, 7; RWG, December 1910, 1-2. The NSW Industrial Act of 1912 embodied a schedule which explicitly exempted certain rural industries from the operations of the Act. In August 1916 the Holman ALP government introduced a Bill that wiped out the exemptions and the Holman Nationalist government shepherded the legislation through the State’s Legislative Council in 1917, much to the FSA’s horror.

[29] Land, 22 March 1912, 4; Sydney Stock and Station Journal, 19 July 1912, 3.

[30] SMH, 22 October 1913, 12.

[31] Daily Advertiser (DA) (Wagga), January-April 1914, passim; Pastoral Review (PR), 16 March 1914, 232 and 15 April 1914, 309 and 333; Rutherglen Sun and Chiltern Valley Advertiser, 13 March 1914, 5; 17 March 1914, 3; 20 March 1914, 5; 24 March 1914, 2 and 17 April 1914, 2.

[32] Land, 2 January 1914, 7-8 and 20 February 1914, 6-7; PR, 16 February 1914, 102.

[33] Land, 27 January-February 1914, passim; PR, 16 March 1914, 232 and 293; Wagga Wagga Express, 23 April 1914, 2.

[34] F&S, 10 March 1914, 2; SMH, 12 January 1914, 8 and 15 January 1914, 10; Land, 30 January 1914, 3 and 6 February 1914, 7. The wharf labourers were not held in high regard by the farmers. The following appeared in the F&S, 3 April 1914, 1: ‘The wharf labourer is not by any means the highest type of man. His fitness for this particular work lies in the mass of muscle in his back and limbs, and in that alone. He may be a Dago, a Dutchman, or a Jamaican negro; he may be illiterate and with the mental development of an aboriginal; he may have neither manners nor morals; he may, in fact, be little more advanced in the evolutionary scale than a gorilla. Yet if he has [a gorilla’s] physical strength he has all, or nearly all, the qualifications required in a wharf labourer’.

[35] PR, 15 January 1914, 5 and 16 February 1914, 105; Land, 30 January 1914, 3.

[36] F&S, 17 February 1914, 5; Sydney Wool and Stock Journal, 20 February 1914, 6.

[37] Land, 24 April 1914, 7; Wagga Wagga Express, 21 April 1914, 3 and 23 April 1914, 2.

[38] PR, 15 May 1914, 463.

[39] Kyneton Guardian, 11 June 1914, 2; Age (Melb), 13 June 1914, 14; Ballarat Star, 15 June 1916, 1.

[40] Scott, Australia During The War, 665-667; SMH, 28 January 1916, 8; 10 October 1916, 9; Argus (Melb), 19 May 1916, 5; Age (Melb), 7 November 1916, 6.

[41] Traders’ Defence Association: SMH, 14 March 1916, 10 and 29 May 1916, 10. National Union: U/121/21, General Manager’s Correspondence, Union Bank of Australia, ANZ Group Archives.

[42] PR, 16 October 1916, 1001-1002.

[43] SMH, 17 November 1916, 6.

[44] PR, 16 December 1916, 1143. The quote is from 16 October 1916, 909.

[45] Turner, Industrial Labour and Politics,107-109; W.M. Hughes to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, 13 November 1916, National Archives of Australia (NAA), CP 78/31, 1916 and 29 November 1916, NAA, A2, 1917/3509.

[46] PR, 16 March 1917, 233-234.

[47] Herbert Brookes, President’s Address 1918 [The Associated Chambers of Manufacturers of Australia] (Melbourne: Sands and McDougall, 1918), 14-15.

[48] Land, 10 August 1917, 13.

[49] SMH, 10 July 1917, 6.

[50] Royal Commission on the Wheat, Flour and Bread Industries – First Report (Canberra: Government Printer, 1934), 11; Wheat Marketing Act 1915. Balance Sheet and Statement of Accounts of the Victorian Wheat Commission to 30th June 1919, with Appendices (Melbourne: Government Printer, 1919), 13; DA, 27 July 1917, 2; F&S, 27 March 1917, 7.

[51] PR, 15 January 1916, 32.

[52] PR, 15 January 1916, 6-7; Australian Worker (Syd), 6 July 1916, 18.

[53] Age (Melb), 17 June 1916, 13.

[54] Age (Melb), 17 June 1916, 13.

[55] D.C. Winterbottom, Weevil in Wheat and Storage of Grain in Bags: A Record of Australian Experience During the War Period (1915 to 1919) (Adelaide: Government Printer, 1922), 7-17; Royal Society of NSW, Sydney, Presidential Address by the President J. Burton Cleland, May 1st 1918, issued September 5th 1918 (Sydney: The Society, 1918), 135-155.

[56] Country and city newspapers and union and farmer publications carried detailed reports of all the strikes throughout 1916-1917.

[57] [1917] AR, 302-315; Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (GGNSW), 29 June 1917, 3329. Farmer organisations were horrified Heydon granted lumpers £1 a day. See, Land, 1 June 1917, 9.

[58] Wedderburn Express and Korong Shire Advertiser, 1 June 1917, 2; Dunmunkie Standard, 8 June 1917, 3; Argus (Melb), 15 June 1917, 4.

[59] [1917] AR, 302-315; GGNSW, 2 November 1917, 6012-6013.

[60] Argus (Melb) 2 June 1917, 19; Land, 8 June 1917, 9.

[61] Construction and Local Government Journal (Syd), 26 June 1917, 18-19. E.J. Holloway, The Australian Victory over Conscription in 1916-17 (Melbourne: Anti-Conscription Jubilee Committee, 1966), 3 claims 30,000 AWU members and ‘nearly’ 20,000 ARU members enlisted.

[62] For the Wheat Board/Minister see, F&S, 15 June 1917, 7. For Marrer see, DA, 15 June 1917, 2 and 7 July 1917, 3; Land, 27 July 1917, 11; PR, 16 June 1917, 513.

[63] Holme, The Strike Crises, 61A, 83A, 141A -146A; F&S, 14 August 1917, 4 and 17 August 1917, 5.

[64] Land, 17 August 1917, 12 and 28 September 1917, 2.

[65] For Holme see: Daily Examiner (Grafton), 11 September 1917, 4. For the Railway Inspector see: Northern Champion (Taree), 29 August 1917, 2. Advertisements calling for volunteers were placed in Sydney daily newspapers, see: Holme, The Strike Crises, 20A and Appendix 6.

[66] Dungog Chronicle, 24 August 1917, 6; Singleton Argus, 18 August 1917, 4.

[67] Land, 10 August 1917, 13. DA, 31 January 1917, 3 reported on George Beeby opening a Labour Exchange in Wagga. Beeby was reported as stating that, ‘There is little surplus labour in rural districts at present, but there is no doubt of its existence in the city’. There were few unemployed men in Wagga, see: DA, 31 January 1917, 3; 16 May 1917, 3; 30 August 1917, 2; and 4 September 1917, 2.

[68] Holme, The Strike Crises, 50A-57A; F&S (Sydney), 31 August 1917, 4.

[69] ‘List of Strike Volunteers 1917’, Farmers and Settlers Association (NSW) Collection, University of New England Heritage Centre, V851; F&S, 14 August 1917, 4; 17 August 1917, 5; 21 August 1917, 4; and 24 August 1917, 4.

[70] Warwick Eather, “From Red to White: Wagga Wagga, 1890-1990”, Rural Society, 10, no. 2 (2000), 195-214; Andrew Moore, “The Tyranny of a small town: Cowra in 1976”, Australian Studies, 17 (April 1992), 25-29; Don Aitken, “’Countryminded-ness’: The Spread of an idea”, Australian Cultural History, eds. S.L. Goldberg and F.B. Smith, (Melbourne: MUP, 1988), 50-57.

[71] Farmers’ Advocate (Melb), 17 August 1917 and 21 September 1917, 2.