TUTA: Early History, Learning Methodology,

and Trigger Films

Des Hanlon and Warwick McDonald

TUTA – formally the Australian Trade Union Training Authority – was created with the passing of the Trade Union Training Authority Act by the Australian Parliament and proclaimed on 8 September 1975. This was two months before the dismissal of the Whitlam government but it had its genesis at least a decade earlier.

Background

Australia has had a long history of trade unionism dating back to the 1850s. Unionism started with separate unions for skilled crafts and tradespeople, then spread to generally less-skilled workers, with the creation of unions like the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the Federated Miscellaneous Workers’ Union (FMWU). Unionism then rapidly spread into public sector employment and the private sector ‘white collar’ and professional workforce immediately following WWI. By the 1960s this growth had mushroomed, with several hundred federal and state unions registered. While some were quite large, most had very small memberships and many were only registered in one state. W.P. Evans outlined that in 1967 the ACTU had 98 affiliates, the Australian Council of Salaried and Professional Associations (ACSPA) had 39, and the Council of Commonwealth Public Sector Organisations (CCPSO), 26.[i] This made a total of 163 unions affiliated to a peak union council in 1967 – and this didn’t include the dozens of other un-affiliated or single-state registered unions and perhaps hundreds of state branches of federal unions that were also separately registered in many of the states.

This fragmentation did not foster strong organisations capable of dealing with large, well-resourced employers, governments, and industrial relations tribunals in a period of accelerating workplace change. But there were a few senior union officials who wanted to do something about this. They included: Ken McLeod, Federal Secretary of the Australian Insurance Staffs’ Federation (AISF); Bob Garlick, Secretary of the Civil Airline Operations Officers’ Association (CAOOA) [the air traffic controllers union]; Bill Richardson, National Secretary of the Australian Telecommunications Employees’ Association (ATEA), who later became ACTU Assistant Secretary; Paul Munro, National Secretary of the Council of Commonwealth Public Service Organisations (CCPSO) – soon to be renamed the Council of Australian Government Employee Organisations (CAGEO); Bill Latter, Secretary of the WA Fire Brigade Employees’ Union and the WA Fire Brigade Officers’ Association and later President of the Trades & Labor Council of Western Australia (WATLC); Jack Baker, Secretary of the Union of Postal Clerks and Telegraphists (UPCT); and Harry Krantz, South Australian Secretary of the Federated Clerks Union (FCU).

They began to campaign for union activists and officials to receive proper training. Many of these (mainly white collar and/or public sector) union training pioneers attended and helped to run annual summer schools at the ANU. The ACTU at its 1967 Congress determined that as part of a union affiliation fee increase, it would fund the employment of an Education Officer. Two years went by. Following his election as ACTU President at the 1969 Melbourne Congress, Bob Hawke finally moved to fill the position as part of the (then tiny) ACTU staff.

Peter Matthews, who had been employed by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in Britain, but by then an adult educator with the University of Sydney’s Department of Adult Education working in heavy industry in Newcastle and Wollongong NSW, was appointed ACTU Education Officer in April 1970. In this role, he was to co-ordinate the union summer schools. Matthews was also then to become Liaison Officer of the Interim Committee of the National Council for Trade Union Training (hereinafter referred to as the Interim Committee) and later National Executive Officer of the Interim Committee in January 1975. Matthews was subsequently appointed TUTA’s first National Director when the Australian Trade Union Training Authority Act legislatively established that body.

An Oxford graduate, Matthews – with the support of these progressive union officials – had promoted and conducted a series of trade union summer schools that had started in 1967 with enrolments of up to 150 union representatives. These schools allowed union representatives from widely different backgrounds to meet and hear lectures from labour economists, labour lawyers, progressive academics and experienced union administrators that covered broad subjects such as economics, labour law, and the challenges posed to unions by accelerating workplace change. Small group syndicate work gave participants the opportunity firstly, to hear from an ‘expert’ in plenary sessions, then discuss and problem-solve set tasks and projects. Small-group collaborative learning and the more democratic term participants – rather than students or trainees – were changes that became central to the participative learning style – or pedagogy adopted by TUTA from 1975.

In the wider labour movement, agitation for the idea of publicly-funded trade union training was beginning in the late-1960s – near the end of the 23-year reign of Liberal/Country Party government that had begun in 1949. Unions and the Labor Party began to push for public funding of union training through an independent stand-alone quasi-autonomous non-government organisation (QANGO). QANGOs were not popular with senior public servants for their relative autonomy and TUTA was to be an uncomfortable fit for some senior federal bureaucrats.

ALP Policy and the Key Role of Clyde Cameron

ALP policy, adopted at its National Conference in Surfers Paradise in 1973, called for an independent trade-union-controlled body to be established to provide trade union training. Its advocates pointed to the substantial federal funding of nascent business colleges for managers in several universities and support for both the Australian Institute of Management (AIM) and the Administrative Staff College at Mount Eliza near Melbourne. Championing this policy was the Minister for Labour and Immigration, Clyde Cameron MHR – a former shearer and Secretary of the AWU in South Australia. Cameron was driven by his belief that the relatively splintered, small-scale trade union movement needed to become more economically and industrially competent as well as administratively more professional. Cameron also passionately believed that unions should train their job activists so they could play a larger role in the running of their unions. Cameron had been appointed Minister for Labour and Immigration in the Whitlam government elected 7 December 1972 and moved quickly to establish a body that was later to become known as TUTA in September 1975.

However there were to be many hurdles in passing the TUTA Act – not least the huge back-log of reforming legislation proposed by ministers of the new Labor government that followed 23 continuous years of conservative rule and a pent-up clamour for reform and change. Most ministers had substantial reforms in mind and this meant that the trade union training legislation, while broadly supported, had a lot of competition for Cabinet attention.

Cameron presented his proposals to Cabinet for an independent authority to be established to provide for a national training college and training centres in each state. Cabinet unanimously adopted these proposals on 3 November 1973. But given that enabling legislation would not be available before March 1974, it agreed that as an interim measure, and following consultations with the union peak councils, a National Council for Union Training be established with a budget of $3 million pa – with such funds to be provided from the budget of Cameron’s Department of Labour and Immigration.

There were to be further delays in processing the legislation. The conservative parties and their supporters, having never really accepted their 1972 defeat (believing it to have been merely a mistake by the voters) and alarmed by the large suite of reforming legislation the government proposed, forced Whitlam to call a double dissolution election in 1974. This resulted in the ALP being returned, but with a narrower majority.

Crucially, in 1973 and 1974 the OPEC oil-producing countries increased the international crude oil price from US$3 per barrel in October 1973 to US$12 per barrel by March 1974 – a 400% increase. This created high inflation everywhere in the world, including in Australia, where the CPI soared. Virtually all western governments were economically destabilised and many subsequently defeated. Internal pressures and the ‘Khemlani Loans Affair’ (in which Cameron was said to have been peripherally involved), further destabilised a government with a small majority. The problems intensified when the Senate blocked supply late in 1975. The prospect of a financial crisis gave Governor-General Kerr the excuse he needed to dismiss the government on Armistice Day 11 November 1975. Fortunately for the advocates of public funding for union training, Clyde Cameron had been able to have the TUTA-enabling Bill passed in both Houses by 2 June and proclaimed two months later on 8 September 1975 – barely two months before ‘The Dismissal’.

The Australian Council for Union Training

and the Interim Committee

Following consultations with the union peak Councils the ACTU, ACSPA and CCPSO (later CAGEO), Clyde Cameron established an Australian Council for Union Training, together with Union Training Advisory Committees in each state. Prior to TUTA being formally and legislatively created in September 1975, there was established in November 1973 a body with the catchy title of the Interim Committee of the National Council for Trade Union Training (hereinafter referred to as the Interim Committee). This committee was responsible for funding union-approved programs prior to TUTA being formally and legislatively created. Members of the Interim Committee had been among the pioneers of Australian union education through their promotion of the union summer schools.

When Peter Matthews was appointed Liaison Officer (and later National Executive Officer) to the Interim Committee, both the Council and the Interim Committee were chaired by Dr Ian Sharp, Secretary of the Department of Labor and Immigration (because funding had been provided from the Department’s budget prior to TUTA being separately established). It included AISF Federal Secretary Ken McLeod representing ACSPA, ACTU Vice President Cliff Dolan, CCPSO Vice President Bob Garlick, WA Fire Brigade Employees’ Union and WA Fire Brigade Officers’ Association Secretary Bill Latter, and Peter Nolan of the Victorian Trades Hall Council (later ACTU Secretary), among others.

Of the $3 million per annum Cameron provided as direct funding from the Department of Labor and Immigration to the Interim Committee, the initial allocation was $500,000. Cameron later claimed that he had arrived at the total sum by multiplying the 150 Federal electorates by $20,000.[ii] This funding enabled the appointment of the first staff in January – March 1975, capital to procure equipment and training aids, and recurrent funding to conduct the first training courses nationally and in each of the capital cities.

In March 1975, Interim Committee National Executive Officer, Peter Matthews was joined by two Executive Officers, Des Hanlon and Warwick McDonald, and a Director for each State Training Centre. Alphabetically by state these were: in NSW, Michael Johnston; in Queensland, Frank Doyle; in South Australia, Phil Drew; in Tasmania, Sean Kelly; in Victoria, Geoff Fary; and in Western Australia, Michael Beahan. These were the first nine appointees of the body what would soon become TUTA.

Pedagogy: The Times They Were a-Changin’

The pedagogy of the Interim Committee’s courses was influenced by both the times and by the trainer-training courses conducted for it by the trainers of the Department of Labor.

The emerging ‘Baby-Boomer’ generation began to come of age and exert its presence from the mid-1960s. They were influenced by the rise in popularity of folk and so-called ‘protest’ music, especially once Bob Dylan (and other artists like him) fused his incisive poetry and folk music with rhythm and blues. Raunchy, loud and rebellious, R&B music certainly inspired the authority-challenging Boomers. Most had only experienced top-down, teacher-centred teaching at school, vocational and tertiary levels of the ‘chalk and talk’ variety. Many were also radicalised by their opposition to the American war on Vietnam and to the associated military conscription based upon a lottery. Political authority was being challenged all around the world with large-scale student actions in Paris in May 1968 rapidly spreading to the USA and many other western countries, including Australia. After a hiatus of many decades, a second wave of feminism had begun to mobilise thousands of women internationally, inspired in part by Australian feminist writers challenging male hegemony and perceived sexism.

The Interim Committee’s early courses in 1973-75 responded to this demand for more democratic educational approaches by maximising active learner participation and by sharing authority and experience around the training room. From early 1975, and even before TUTA’s formal establishment, virtually all training rooms featured oval, circular or horse-shoe desk arrangements. Participants introduced themselves to their group, giving their background and what they hoped to achieve from being present. Tutors explained that each participant had a variety of skills and experiences and that these should be shared around the group. As a training session progressed, ‘overhead’ questions were put to groups to answer with tutors trying to ensure all individuals could respond at least some of the time.

This pedagogy was underlined by union trainer-training courses using the training resources of the Department of Labor’s Trainer-Training Unit in Melbourne, especially trainers John Rudolph and Mick Burton. They emphasised that a learner-centred approach would maximise the learning outcomes, the relevance of the subject matter, the ‘buy-in’ of the group and thus the quality of learning. Adults learn better when they are engaged in active learning and when the subject matter is relevant to their known experience. So these learning techniques were strongly emphasised.

Union representatives usually don’t need to be encouraged to speak up. On the job they are often involved in meetings of all kinds, co-ordinating worker claims, defending individual workers, forcefully putting up issues to managers and advocating positions to authority. (Labour Department trainer Mick Burton once asked Warwick McDonald… ‘don’t they ever shut up?’ when he first encountered the volubility and self-confidence of union representatives in an early union trainer-training course.) But as Clyde Cameron knew, union reps sometimes needed a bit of polish.

From the earliest courses, full-group plenary sessions were quickly followed by smaller group syndicates guided, but not dominated, by tutors. When TUTA was finally established in its national residential college and state capital training centres, there were usually five or six syndicate rooms for every main training room. A session would begin with a presentation from a staff tutor or guest. Issues were then discussed in small groups involving debate and problem-solving. Reporting back to the plenary full course group usually took place in groups as small as five or six people, with report-back roles shared around.

This participatory learning atmosphere required training aids. Because most people perceive most of their information visually rather than aurally, TUTA training staff were required to always use visual aids and visiting experts were encouraged to do so as well. Small groups also had to report back with visuals – usually overhead projector transparencies or butcher’s paper summaries of their work. These became common learning methods later but were almost unique back then.

Trigger Films and The Claim

Some training films were used in courses to illustrate basic union skills and issues such as representation, reporting back, minute-taking and communication skills. Notably, an excellent black and white production from the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada called Do Not Fold, Staple, Spindle or Mutilate (1967) was widely used. The storycentred on a Canadian paper-making line producing computer punch cards and the difficulties faced by an older union rep trying to keep up with workplace change. But given that training aids work best when they are seen as realistic, relevant and similar to the learner’s own environment or experience, the Canadian accents in ‘Do not Fold…’ proved a distraction. So the Interim Committee agreed to make a series of Australian union training films.

Trigger Films

Des Hanlon was given the task of developing the purpose of each film and to act as TUTA’s Technical Advisor to Film Australia, another Australian government statutory authority contracted to make them. Initially, the Interim Committee decided that it would finance three ‘trigger’ training films – designed to trigger debate, small-group discussions, role-play practice exercises and thereby promote active learning. One of the early leaders in union education was Colin Macdonald, Trade Union Education Officer of the WEA (South Australia), who had successfully run correspondence programs for union members and who was quoted, on reviewing the first three TUTA films, ‘I thought we would have several failures before we had a success, given we are a new organisation …’.

To the first three were then added three further trigger films, so the Interim Committee had created a series of six short training films on various workplace situations. Of the total of eight films that TUTA commissioned during its first five years, the average running time for most – the six trigger films – was ten minutes or less.

In the words of Film Australia’s promotional brochure, the trigger films were about: ‘communicating at work; the need to get the facts right; to get the words right; and to get the result right’. These were:

Interview (9 minutes) dealt with the delegate’s problem of selecting information, and sorting facts when communicating a complaint;

Facts (12 minutes) was about the need to be responsible when reporting member complaints to a union organiser;

Report (9 minutes) showed the dangers faced by employees jumping to poor conclusions and second-hand or unreliable information about management’s intentions;

Changes at the Office (11 minutes) covered persistent rumours of imminent sackings;

Will you join? (10 minutes) covered different approaches to encouraging an employee to join;

A Personal Matter (9 minutes) touched upon a seemingly unsympathetic attitude from a union representative about a migrant worker’s problems. It raised issues of prejudice, justice and fair play at work.

TUTA (10 minutes) was not a trigger film, but described the Authority’s work in conducting courses for all levels of union activity and demonstrated the training methods used.

Not all proposals for films were approved by the Interim Committee. It declined to make a trade union history film. This proposal was for a film with a proposed budget of $50,000. The Committee couldn’t finally decide on whose version of trade union history they wanted to tell. After this disagreement couldn’t be resolved, the Committee decided that no history was better than a compromise. The un-spent budget was returned to Consolidated Revenue.

The Claim

The exception to the trigger films was a film called The Claim. Within Film Australia circles it was referred to as ‘the silent feature’, as it ran for 80 minutes. The structural form of The Claim was a series of three short extracts that reflected, first, the initial development of a log (or list) of claims, second, the attempts at direct employer negotiations and, finally, the arbitral processes and outcomes that were the norm in Australian industrial relations when negotiations didn’t resolve all issues. The Claim was designed to be paused at appropriate stages and shown in short pieces of each of these three segments.

In a related article, Des Hanlon describes his first meetings with the Film Australia filmmakers and details the production of TUTA’s films. We also pay tribute to filmmaker Keith Gow who wrote the scripts and directed all of TUTA’s films.

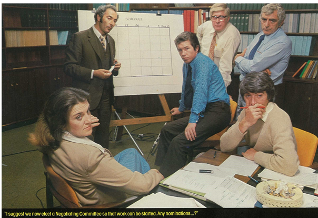

“I suggest we now elect a Negotiating Committee

so that work can be started. Any nominations…?”

Screenshot from TUTA film The Claim reproduced in The Claim,

Film Australia brochure 1975, p. 2.

Endnotes

[i] W.P. Evans in P.W.D. Matthews and G.W. Ford (eds.), Australian Trade Unions, Sun Books Melbourne, 1968, ch. 4, p.117.

[ii] Clyde Cameron, Unions in Crisis, Hill of Content Publishing, Melbourne, 1982, ch. 16, p. 232.