Tim Ayres

Address given at the opening of the exhibition on the Great Strike, Eveleigh Carriageworks 17 July 2017

I’m grateful for the invitation to speak and particularly honoured to be here at Carriageworks, a vast industrial facility repurposed by a Labor government into a vibrant arts precinct.

Much of the renovation work was performed by long term unemployed men and women from Newtown, Redfern and Waterloo employed under the “One Nation” Keating government stimulus package that followed the deep recession of the early 1990’s.

I know this because I was the union organiser for the refurbishing work on this site as a 21 year old. I had no industrial relations experience and they had no experience of work. It was quite a scene.

This building is older than Federation. It was built in the same decade as the maritime strike, the Broken Hill miners’ strike and the shearers’ strike that led to the formation of Australian Labor.

Up until the late 80’s, this place is where thousands of workers built and repaired the machines that made Sydney run. I particularly welcome AMWU delegates from Sydney Trains and UGL Maintrain, who do the same vital work today.

I love the way the remake has embraced the original industrial legacy.

They have created something beautiful from details such as rivets and the rail lines embedded in the concrete floor. I vividly remember in 1995 that there were still anti-Vietnam War posters stuck high on some of these columns.

This place forces us to remember the generations who worked here: the boilermakers, fitters, blacksmiths and labourers. Nobody remembers the foremen. Their work, their experiences and struggle are all a part of this place. I wonder what they would make of Fashion Week.

Isn’t it crucial that we in the labour movement remember their struggle and heroism?

Fundamental to our vision of our past and future is the idea that that working people have the ability to shape history – to make history itself. That is what E.P. Thompson meant when he wrote The Making of the English Working Class – that the English working class was present at its own making – and I think the men and women who went on strike knew what they were doing and the dramatic effect it would have on our history.

We remember the great strike, in part, because the strikers themselves demanded to be remembered. This is the power of the lily-white badge: given to the strikers who refused to return to work.

History matters, and labour history matters even more, and how we write it and who are the players in it is critical.

I can’t imagine we can make much progress as a country if we allow the conservatives to write our history for us. I am deeply unnerved by the jingoism of modern ANZAC celebrations, people wrapping themselves in flags and the commercialisation of ANZAC imagery by supermarkets – Woolworth’s “fresh in our memories” campaign is particularly revolting.

I grew up in a conservative country town where ANZAC was commemorated, not celebrated, with all the solemnity and dignity we could muster. It still had all the trappings of overt militarism, but the message from veterans and the RSL was all the more real because they were there – “never again”.

It does matter who writes the history, and as we slide into a more dangerous world we could do with a little less jingoism and militarist triumphalism in our story telling and a lot more labour and social history.

The other side saw the Strike for what it was. George Pearce, the Minister for Defence wrote that it was “the aftermath of the Conscription Referendum and the recent Elections” and Billy Hughes the “Labor rat and war-monger “, according to Clark, accused the strikers of preferring social revolution in Australia rather than victory in France, which he maintained must be secured before the “maggots of  revolution ate too deeply into the foundations of capitalist society.”

revolution ate too deeply into the foundations of capitalist society.”

What a bastard Hughes was.

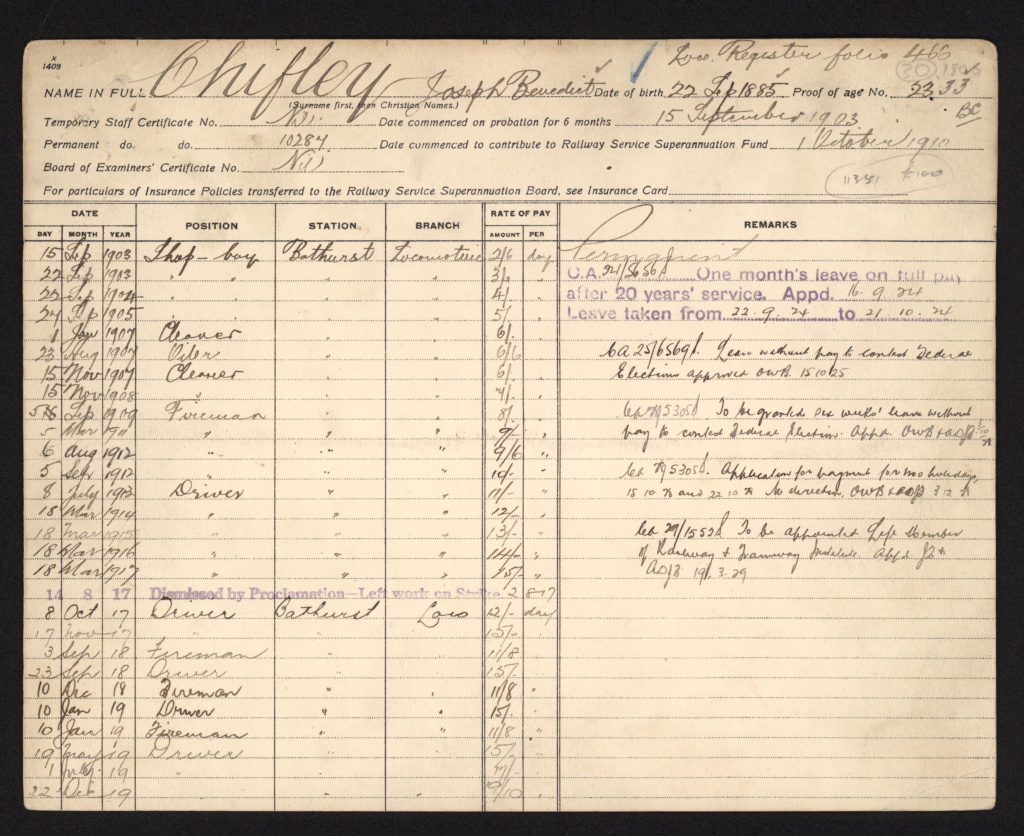

Chifley and Eddie Ward were active in the Strike and were at the core of subsequent Commonwealth Labor administrations that re-wrote the Australian social contract. Joe Cahill and Bill McKell worked here too, and in NSW successive Labor governments drove social and economic change that vastly improved life for working people. I don’t think it’s too fanciful to imagine that their common experience of the Great Strike forged their commitment to equality, that the strike itself was that engine of political change.

We owe the 1917 Centenary Committee an enormous debt of gratitude for allowing us this opportunity to reflect, to tell the story, to commit to learning the real labour history of Australia and to thinking clearly about our modern challenges.

One of those contemporary challenges has to be the right to strike.

Australia is a country that has been defined by unions and union action, by a total lack of deference to our ‘betters’ in management, government or authority. Our history – Eureka, Kelly, the Gurindji walk-off, the refusal of wharfies to load pig iron for Japan, the Green Bans and boycotts of Indonesia and South Africa – and our literature – of Henry Lawson, Ruth Park and D’Arcy Niland’s Shiralee – all of these put courage in the face of adversity and the labour movement at the heart of not just our national history and culture, but at the heart of our national character.

But today the right to withdraw our labour, a deeply human right, is so legally circumscribed that it doesn’t really exist at all.

Why have we become so timid? What would the 95,000 men and women who went on strike in 1917 have thought of this quiet abandonment of the right they fought so hard for?

The first step back into this debate is to recognise that for many workers the right to strike for better wages or a better deal at work is in real terms gone, and that makes our society more unequal.

The second vital step is to recognise that this right is not just a narrow economic right, but a political and social right that is inalienable in any decent democracy.

The moments in our history that speak to labour movement values are when wharfies, or airline workers or Aboriginal stockmen walk off the job over a democratic principle. All of this would be illegal today – workers would be forced back to work by the State and armies of lawyers.

There is no real progressive politics without this right. You cannot support the Green Bans, or oppose apartheid, without recognising the importance of strikes.

On the 100th anniversary of the Great Strike we should commit ourselves – let’s return this right to ordinary Australians and win back the right to strike.